I’ve been thinking a lot on GraphQL “Schema Stitching” these days. At its core, Schema Stitching is the art of composing multiple GraphQL Schemas into one GraphQL Schema. As you can imagine, this can be great in a service oriented architecture, where each team would take care of a part of the schema, iterating quickly on it, and at run time, some sort of API gateway would “stitch” all these schemas to present a single API to clients.

This concept, starting to be adopted in production more and more, is covered a lot in discussions, proof of concepts, and general hype around GraphQL. In fact, by reading some of the things on it, it is almost as if this is the true power of GraphQL. I haven’t been totally convinced by that yet. After all, GraphQL origins are found coming from an architecture that is quite the opposite of the service oriented one at Facebook, having a huge monolithic schema.

In this post, I hope to show where I think the tradeoffs are with schema stitching, and a middle ground I’ve been imagining.

API Gateways

API gateways are always quite complex pieces of infrastructure, but GraphQL ones come and add some extra difficulties on top. A ton of things can be handled at the gateway level, such as authentication, rate-limiting, transformation, logging etc, but in this post, we’ll focus more on the API layer itself.

With typical HTTP APIs, API Gateways will usually act as a “simple” reverse-proxy on top of your different services, each serving different resources. The gateway might apply transformations to the payloads, combine different sub-domains, etc. Some of them do aggregations, for example using the result of two different services for one resource at the gateway level. We’ll come back to this later on.

A major difference in how we design GraphQL APIs is how connected all objects are connected to each other:

type User {

name: String

posts: [Post]

}

type Post {

title: String

author: User

}Now imagine User and Post live on their own schemas, in completely different applications. Clearly, each of the schemas are invalid on their own. For the User schema, it is invalid because the type Post does not exist in the schema. For the Post schema, it is invalid because the User type does not exist.

Hmm, this is slightly annoying already. A first solution to this issue could be to change the way we design the schema. We don’t know the Post type, but we do know we have posts, and we probably have their IDs, so how about this:

# users.schema.sdl

type User {

name: String

postIDs: [ID]

}

# posts.schema.sdl

type Post {

title: string

authorID: ID!

}Now the stitching will work fine, but is that really what GraphQL is all about? With this design, our clients cannot query connected objects in a single query:

query WhatWeWouldHaveLovedToDo {

currentUser {

posts {

title

}

}

}Instead, they have to query first for ids, and then again to hydrate the posts:

query WhatWeEndUpHavingToDo {

currentUser {

postIDs

}

}

query AndThen($ids: [ID]) {

posts(ids: $ids) { title }

}This is far from ideal, kind of loses the whole point of GraphQL and is hard to implement especially if you already had a complex monolithic schema that already expressed these relations with GraphQL.

Note that if you do decide to take this tradeoff, it’s totally fine. For example AirBnB opted for that approach since they already had presentations that worked this way internally. This is totally fair, and poses no problem if we’re aware of the tradeoffs.

Now if we don’t want to accept this tradeoff, we must find another solution.

Classic Schema Stitching

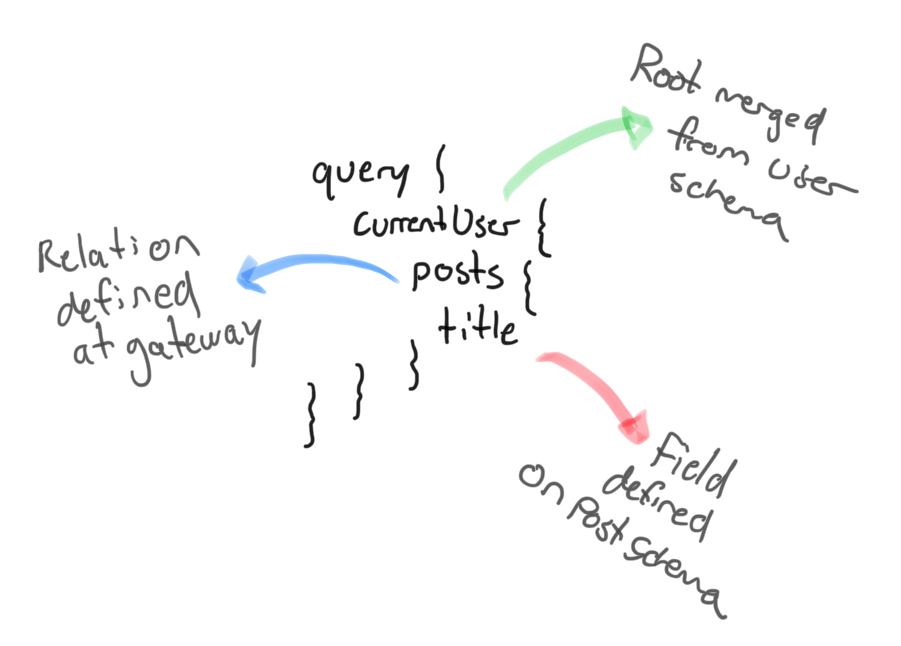

I call classic schema stitching here, what seems to be the current, most common way to make schema stitching work. It kind of looks like this:

The schema gateway takes n number of schemas, merges them together, and extends the result with these “relations” we’ve been talking about. This works well in the sense that each service can be developed without any dependencies on other services, and the final schema is still a well designed schema that allows clients to fetch multiple relations within one GraphQL query. Of course that requires additional “glue” code, here’s what I’m talking about using Apollo again as an example: https://www.apollographql.com/docs/graphql-tools/schema-stitching.html#adding-resolvers

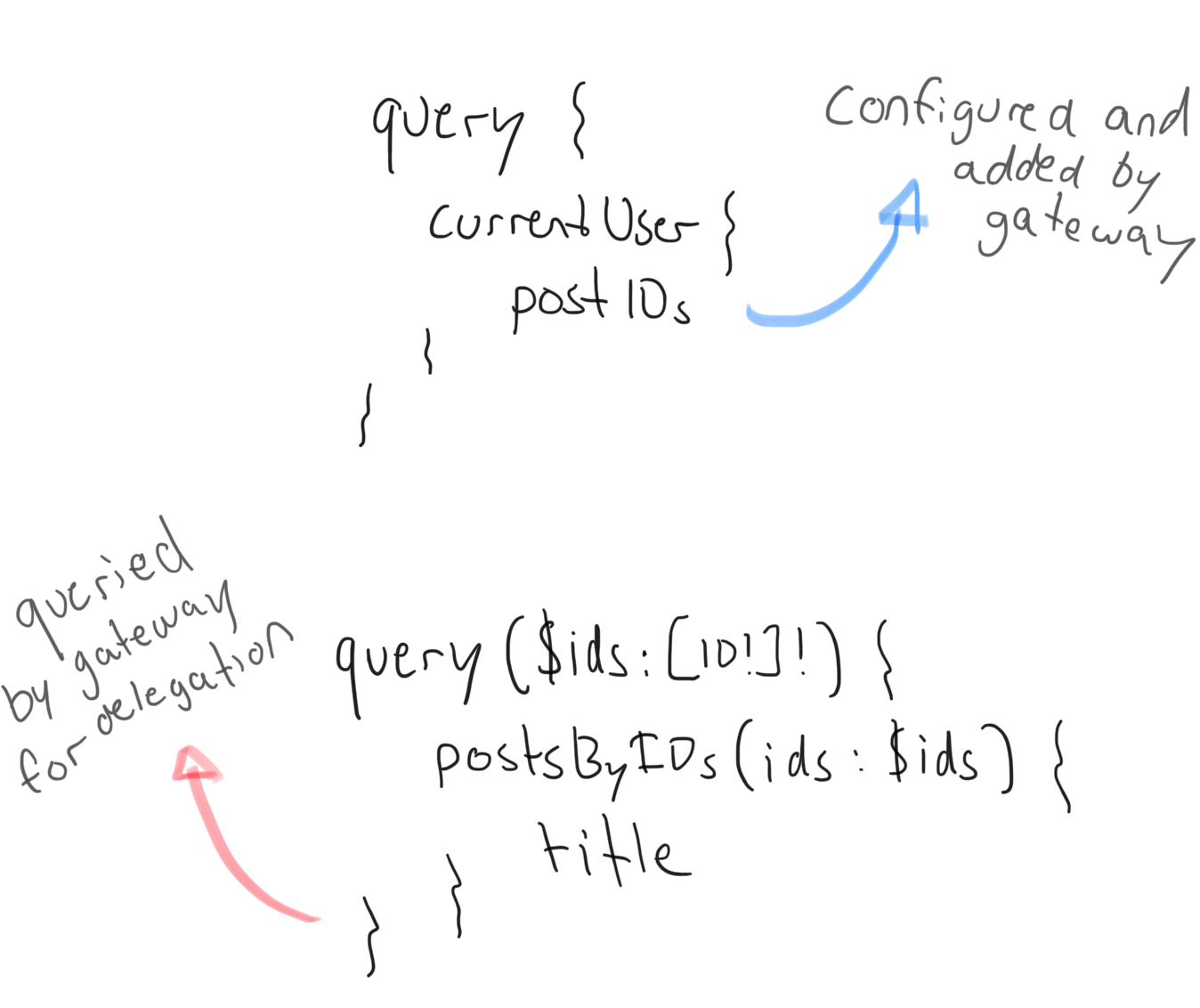

The stitching code lets you add additional data to the query as a prerequisite to fetch the relation (often id or ids), and then what query to execute on the other side to fulfill the relation. The rest of the query is then delegated to the other schema. The query, from an external perspective, looks like this:

In reality, the real GraphQL executed, looks more like this:

In the end, two queries are necessary. But this is transparent to the API client. We had to configure our API Gateway to request the postIDs when asked to fulfill the posts relation, and to execute the bottom query to fulfill the posts requirements. All in all, very cool!

The thing that bugs me a little with this approach is that we started with the intention of decentralizing schemas, having small self contained services and schemas, but in the end, if you imagine a large stitched schema, we end up with a lot of “glue” code at the gateway itself, defining all the important relations there.

Not really a GraphQL problem

I introduced the problem as a GraphQL specific problem, but if we think about it, we can face the same kind of trouble if we start doing aggregations at the gateway level, even for an other kind of API. If we were to define an HTTP endpoint that returns users and posts, but we had only an user endpoint, and a posts endpoint living on another service, we would have similar concerns. One of the concerns with this approach might be that because individual responsibilities are not clear, we will have a tendency to accumulate logic on the gateway side of things, leaving our user and post endpoints more and more dumb, and our API gateway becoming responsible of everything.

This is definitely not an easy problem to solve, but one thing is for sure, just like these aggregations, our initial independent schemas are not so decentralized anymore when we have to glue them together.

My Question

At this point, what is the point of having decentralized schemas when in reality, we need a centralized point to merge and extend the schemas?

Note that we’ve added two steps to most schema changes that link to other services.

- Make schema changes at the service level

- Extend the gateway schema with links to the new changes

To me, that’s far from an ideal developer experience.

Hard Mode

There is probably a solution out there to fully decentralize our schemas, maybe something like this:

Where our gateway could simply merge everything together, and each service would know how to fulfill their dependencies by themselves. To me, this dependency management sounds super complex, but I’m sure it’s possible. That’s for another post. Nothing super new here either though! It reminds me of the whole Orchestration vs Choreography thing.

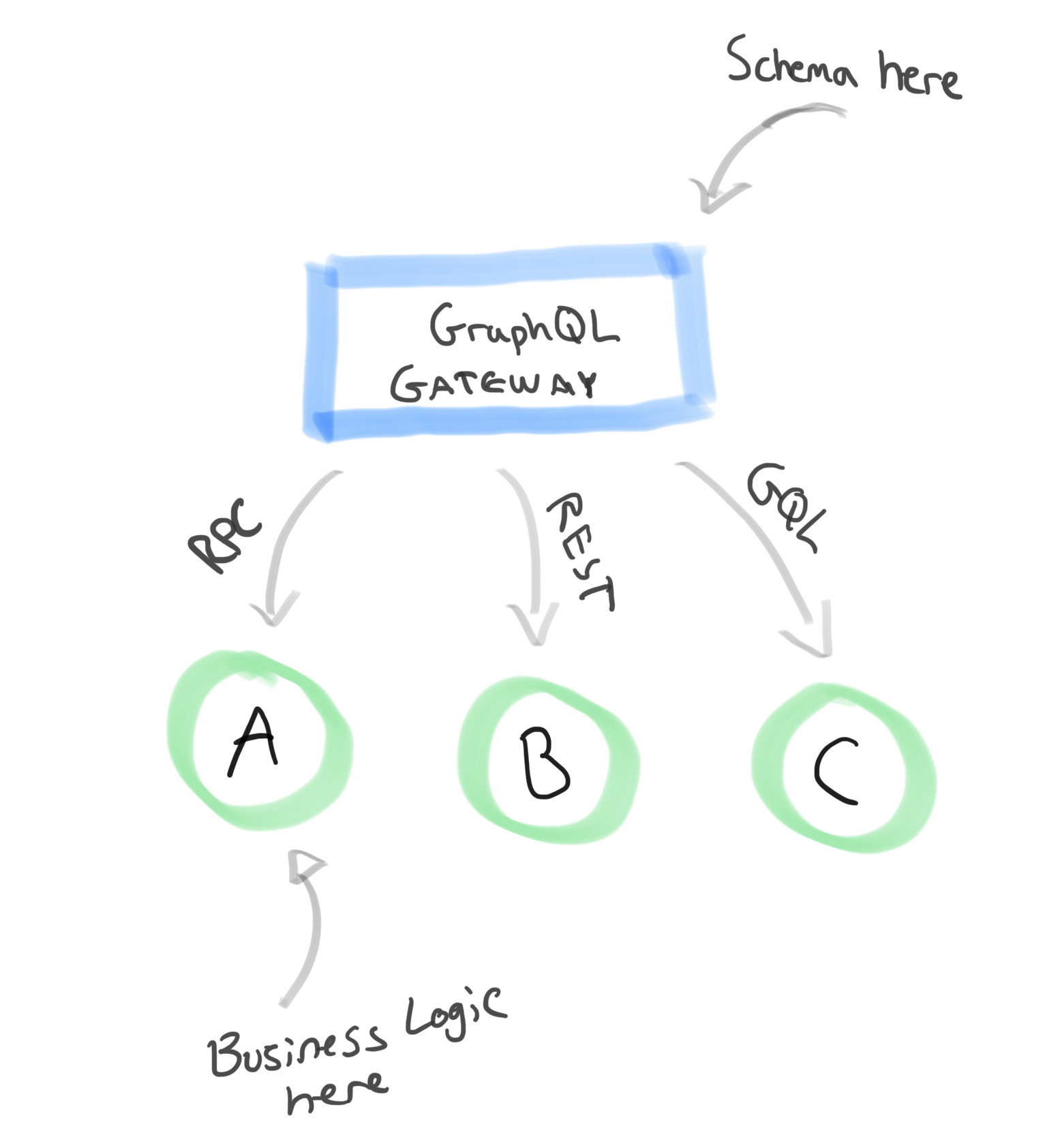

Centralizing the Schema

With all that said, the “schema choreography” does sound scary to implement in an existing large schema and organization. If we come back to the gateway approach with more orchestration, here’s what I would go for: *Centralize the schema, but decentralize execution. - I have trouble seeing the advantage of defining the schema in multiple places if we have to assemble it and write “glue” code anyways at the gateway level. Can we do everything at the gateway then?

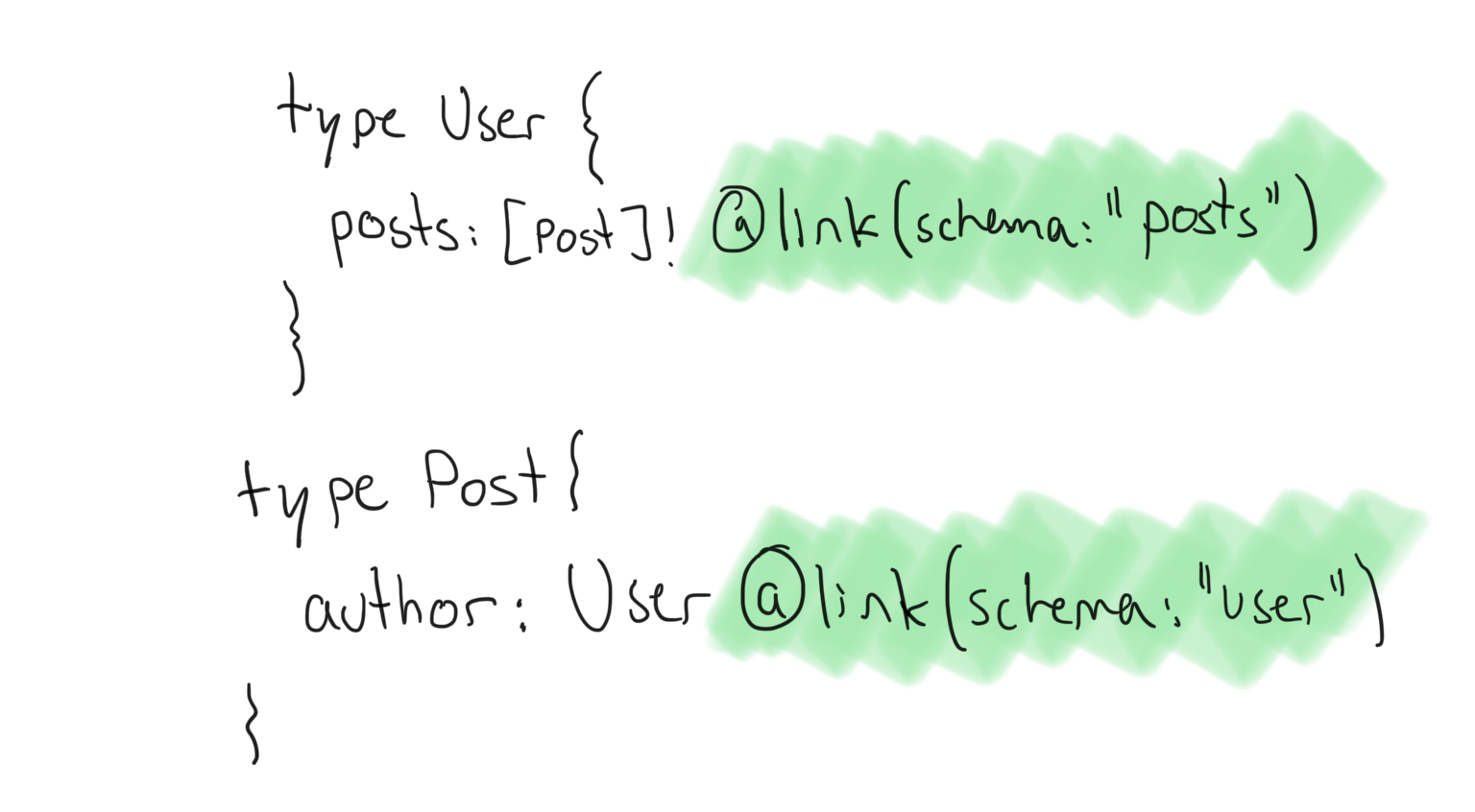

Here’s an approach I’d like to propose:

- Define the schema using the SDL at the gateway.

- Instead of stitching and merging together schemas, have great tooling to enable importing types / fields from certain schemas.

- Design the gateway in a way that minimizes the amount of business logic. That’s a hard one, the “glue” code we talked about needs to exist somehow, and it’s hard to avoid that code to become more than just glue.

- Possibly extend the SDL syntax with directives that allow connecting services together. Auto generate as much code as possible to avoid custom business logic.

- Services can define their interface with anything: grpc, REST, GraphQL, it doesn't matter, we can build the right adapters at the gateway level.

That gives us a few advantages:

- The resulting IDL is found in a single place, it is easier to track down issues, and to view the final state of the schema.

- There’s only one thing to change to make changes to the schema, it’s also more obvious to see what effect the change will have.

- Sharing types, conflicting types are well handled as we control the whole schema. The lack of namespaces makes schema merging tricky, although there are solutions to this.

What we need to be careful of:

- Multiple teams working on a large schema, we lose the autonomy of a fully decentralized schema. As a solution: we can possibly detach part of the schema into their own service, but always manually import those types into the gateway, no automatic stitching.

- We don’t necessarily solve the “business logic at the gateway” problem. As we build this gateway, we have to get the API just right so that the code base can’t evolve this way.

Yep, we’re back at a monolithic schema, but we’re interfacing any services we’d like. This seems like a good middle ground to me right now, but I have a lot more to explore. The whole Orchestration vs Choreography is super interesting and comes with its own set of tradeoffs, both in terms of design and operating the services.

There are multiple valid approaches to exposing a unified GraphQL schema, all of them with their sets of tradeoffs. What do you think of the centralized schema gateway approach? Looking forward to your thoughts on this, thanks for reading! ❤️